The Kobaien

NARA

Sumi: Solid Ink the Kobaien Way

Before the obsession with mecahnical pencils and ball-point pens, people took immense pleasure in writing with brushes and black ink.

Traditional ink is solid, and is dissolved on an as-needed basis by rubbing it in a few drops of water on an inkstone. There are few people who regularly use this method of writing, though children are still taught the basics of calligraphy in school. But it’s is still an important part of Japanese culture, and people often use calligraphy at weddings and funerals.

Ink production originated in China and the techniques were imported to Japan around the year 610. Since Nara prefecture was a seat of national politics, and also home to many shrines and temples, demand for ink was high. It’s said that artisans in Nara began developing ink-making techinques by using the soot collected the from pine resin burned at Kofukuji temple. Ink production spread across Japan, but has drastically decreased due to shrinking demand. But Nara still corners what’s left of the market, shipping over 90% of the country’s ink.

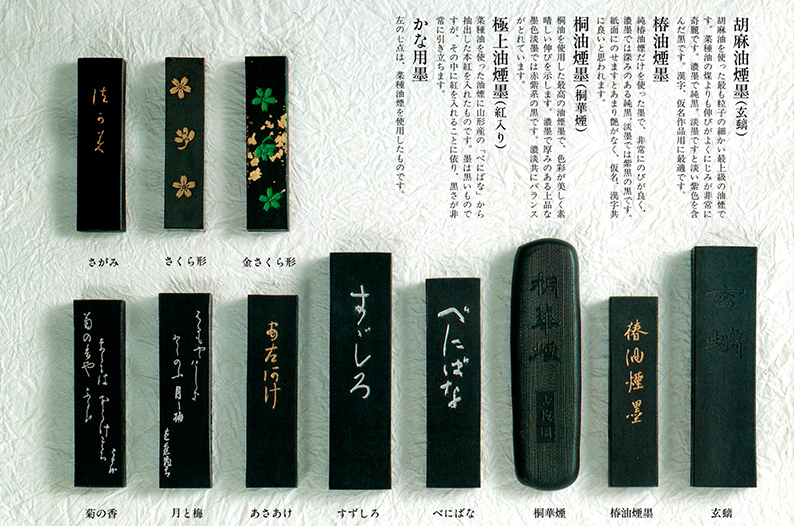

Kobaien has been producing sumi for over 400 years. Established in 1577, they are the oldest ink maker in Japan. They originally used Chinese techniques, but developed their own methods along the way. The company has even won a Chinese client base. While competitors market a cheaper, mass produced product, each piece of Kobaien ink is handmade by 4 to 5 craftsmen. Only three raw materials used: soot, glue, and fragrance.

First, the soot is collected by burning oil. A cloth cover placed over the “candle” catches the soot. The finer the wick, the finer the soot particles. And the finer the soot particles, the higher quality the product. The craftsmen must ensure a consant supply of oil and make sure the wick doesn’t sink. All this while turning the fabric to make sure it’s evenly covered in soot. This understated procedure has a big impact on how the ink turns out. A mechanized process can produce identical soot particles, but natural soot is uneven, and the fine particles take on various shapes and sizes. Calligraphers value this irregular composition, saying it creates a lively expression on paper.

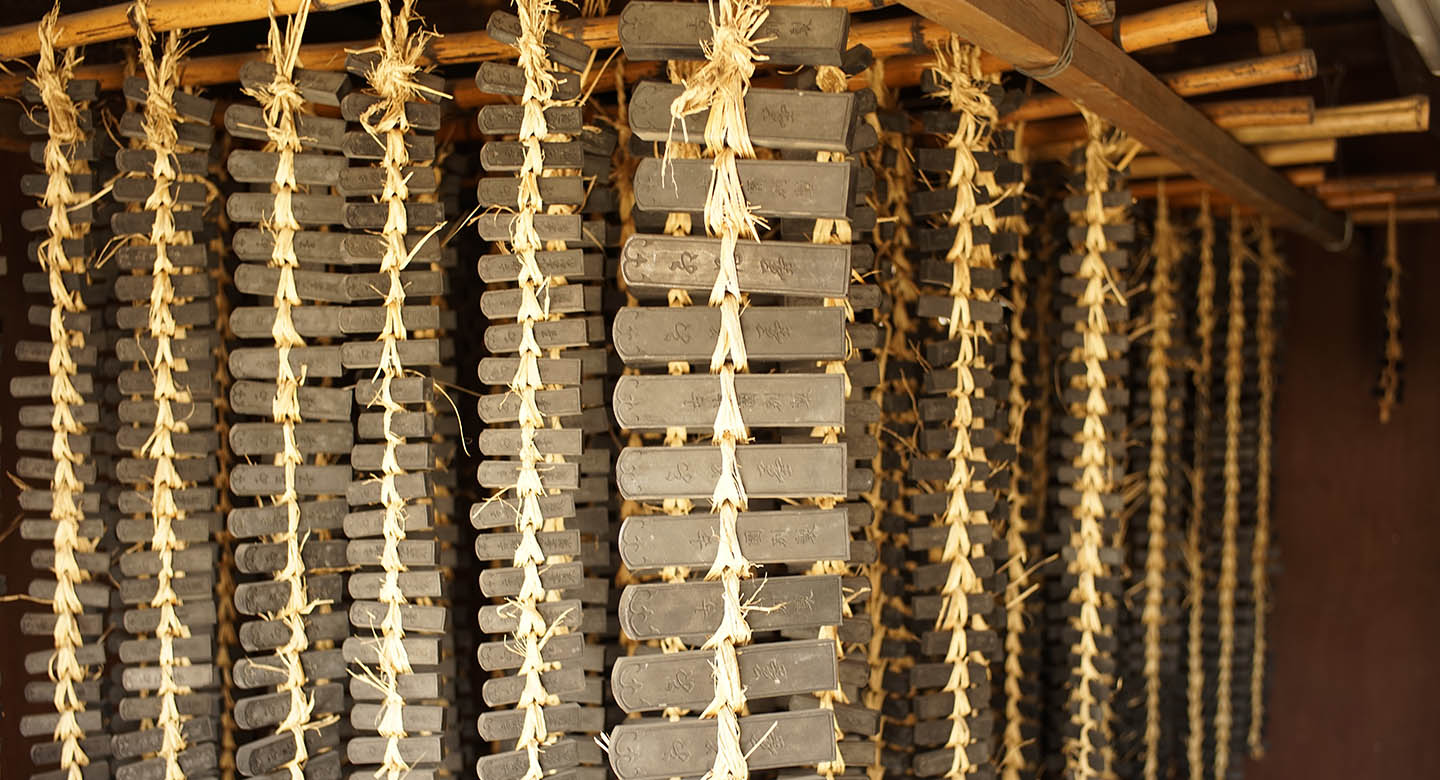

Next comes the most physically demanding part of production. Liquid glue and fragrance are blended with the soot, and the mixture is separated into small balls. These are then pressed into moulds made from pear trees. (The moulds are prized as art objects themselves.) The moulded ink contains moisture and is dried with oak ash. Wet ash is replaced daily with drier ash so the ink dries evenly from the inside out. The ink is then suspended with straw in the last stage of this process.

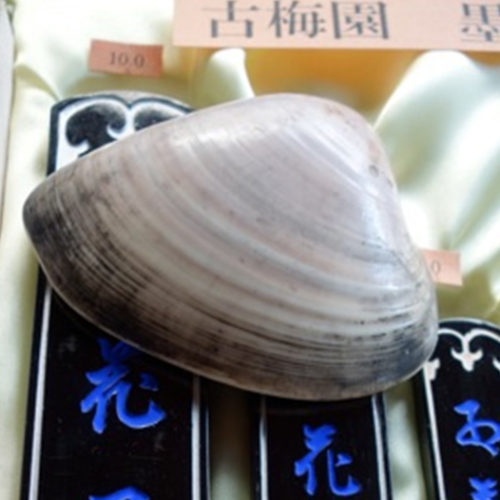

Kobaien‘s flagship product is Safflower Ink. Its glossy surface is created by lightly roasting it in a fire and polishing it with clam shells. In 2015 the company marked their 70,000th piece of ink produced with this technique. And its craftsmen continue to respect this tradition despite the scarcity of quality glue, fragrance, and clam shells large enough for the job. Since the materials used are all natural, calligraphy art created with this ink can retain its original appearance for hundreds of years. Enthusiasts can clear their minds and relax while enjoying the perfume of the ink as they prepare to write or paint.

Ink season runs from November to April, and visitors to Kobaien can try their hand at making sumi. Access to the Meiji-era workshop is offered exclusively to participants, so it’s a very special experience that’s not to be missed.

By Haruka Muta

December 21, 2016

The Kobaien information

Address

7, Tsubai-cho, Nara-shi, Nara

TEL:0742-23-2965

http://kobaien.jp/

- TOPCOLUMNThe Kobaien

- TOPDESTINATIONSNARAThe Kobaien