Korian

Where you can have the entire hotel – and Japan's oldest and stinkiest sushi – to yourself

SHIGA

Indulge in Japan's most exotic sushi

Situated on the shores of scenic Biwako, Japan’s largest lake, Korian is a distinguished establishment that only accepts one group of guests per night. My expectations were high. But I was also worried. Worried because Korian was all about funazushi, reputed to be Japan’s most exotic sushi. I’d never had funazushi, but from what I’d read, I wasn’t sure I was going to like it.

Funazushi is exotic for a number of reasons, the first being that, like me, most Japanese have never even heard of it. Those who have refer to it as “that stinky fermented dish.” Made by preserving fish with cooked rice, funazushi is considered to be the oldest existing form of sushi.

No matter how exotic or historically important it was, I wasn’t keen on having a full course dinner featuring funazushi. If I didn’t like it, would I go starving? I was worried.

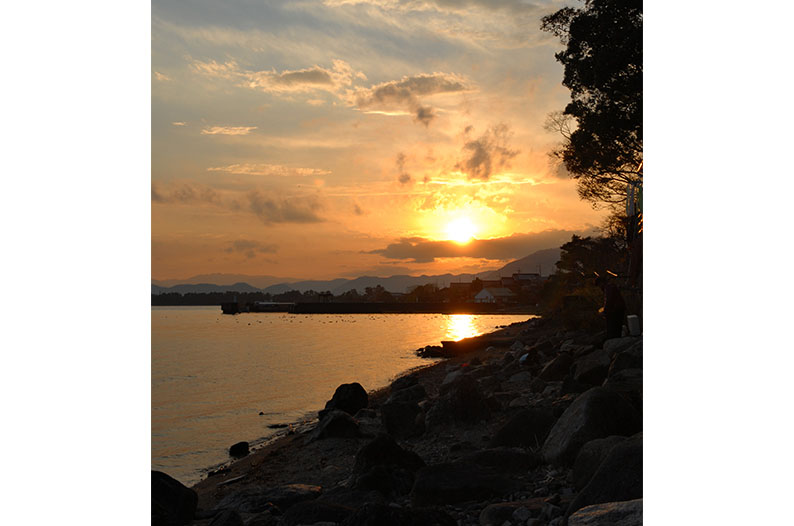

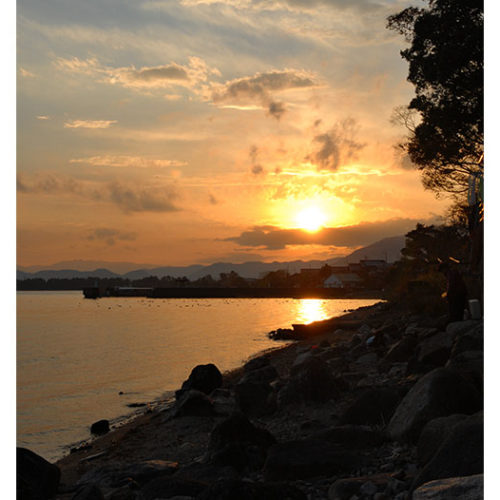

Arriving at the hotel, my worries disappeared in a flash as soon as I entered my room. Through the glass wall, I could see nothing but water and sky. The expansive waterline made me realize how narrow my field of vision had become. My temples loosened and the world suddenly seemed a bigger place. Captivated by the scenery, I synchronized with the waterfowl bobbing on the waves.

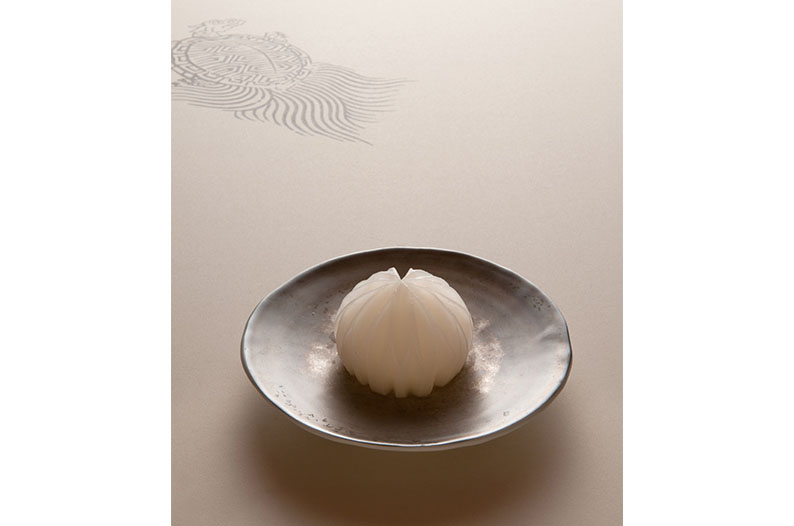

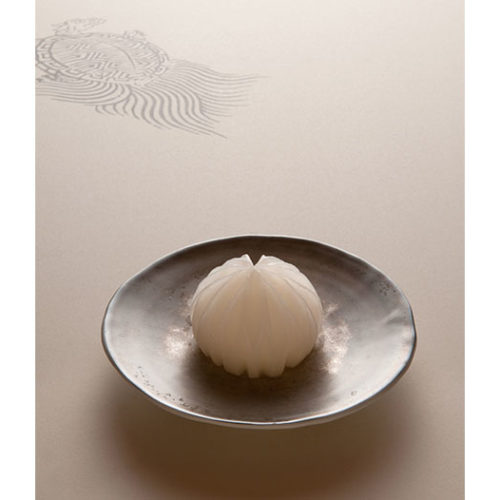

I finally shifted my sight from the window as the proprietress brought me matcha tea. The simple aesthetic of the tea bowl and the accompanying sweets, combined with the proprietress’s sense of hospitality, eased any remaining tension. Equipped with a hand-drawn map of Kaizu, the local town, I set out for a stroll.

As a port city connecting Kyoto to the north, Kaizu flourished during the Middle Ages. All of the town’s buildings, including Korian, are built on a stone wall lining the lakeshore, erected in the 18th century to prevent damage from floods. The statue of an unrecognizable deity was tucked into the stone wall, its eyes and nose crumbled from decades of wind and rain.

Old buildings stood side by side, including a few charming temples. I could feel the breath of the residents intertwined in the town’s history. But the town was quiet. Unlike other towns riding the wave of tourism, Kaizu remained an undiscovered gem.

After my excursion, I returned to my room. As I gazed out at the soft pastels enveloping the darkening Biwako, the proprietress called for dinner. I braced myself for my first funazushi experience.

Funazushi is a type of narezushi, the original form of sushi in Japan. Freshwater fish was preserved by fermenting it in cooked rice, a method brought to Japan 1,500 years ago from mainland Asia, along with the culture of cultivating rice. Although the rice was traditionally thrown out at the end, people began to eat the fermented rice in the Edo period, giving birth to the modern form of sushi.

Funazushi is made by fermenting nigorobuna, a type of crucian carp that’s only found in Lake Biwako. Descriptions of its smell ranged from “strong” to “pungent,” with some going as far as calling it “offensive.” It sounded like the line between rotten and fermented was thin.

It wasn’t pretty, either. The photos I’d seen were slices of fish nestling orange eggs. I hoped that tonight’s dinner wasn’t going to be course after course of those squishy-looking slices.

To my relief, the first dish was an elegant assortment of bite-size appetizers. Funazushi rolled in white mold cheese, and grilled and sandwiched in bread. The delicate presentation guaranteed that I was in for a fine meal, and my senses eased somewhat.

Daringly, I took a whiff. Surprisingly, the smell wasn’t “offensive.” It wasn’t even “pungent.” As I took my first bite, a firm acidic flavour spread across my tongue, followed by a pleasant taste that reminded me of rich cheese. It wasn’t fishy, or overwhelming. Contrary to all expectations, I was enamoured.

And so began the savoury funazushi parade. One delectable dish after another, with a local sake enhancing the flavours. I couldn’t put my chopsticks down.

Midway through the meal, a pasta dish was served. At first glace, it looked like spaghetti with cream mushroom sauce. But there was a sumptuousness that wasn’t cream, or mushroom. It wasn’t funazushi, either. What was it, then? The rice used to ferment the funazushi. I couldn’t get enough of it, and ended up licking my plate. Oh, the privilege of dining alone! Ice cream made with sake lees completed the exquisite meal. I laughed, remembering how worried I’d been that I might not like funazushi.

The man behind the funazushi extravaganza was Kensuke Sazaki, seventh generation owner of Korian and head of Uoji, a funazushi shop founded in 1784.

“For most of the year, nigorobuna live in deep waters. But in the spring, they come to the shore to lay eggs. They used to swim up the waterways to the rice paddies, so it was easy to catch them. Our ancestors made funazushi as a way to preserve the excess catch.”

Today, nigorobuna are caught in the spring and gutted, leaving only the eggs, then cured in salt. In the summer, they’re unsalted and layered with cooked rice in wooden barrels. The lids of the barrels are then sealed until the winter of the following year.

“It’s the lactic acid bacteria in the air that makes funazushi, so the flavour varies from family to family. My job is to create a comfortable environment for the bacteria to ferment and make good funazushi.”

Any unwanted bacteria would change the flavour that his ancestors have protected over the centuries. “So I’m the only one who’s allowed to enter the cellar,” says Sazaki. Normally, funazushi is prepared in the spring and eaten the same winter. But Sazaki insists on a two-year cycle to allow the funazushi to age at a low temperature during the winter. During those two years, Sazaki is the sole guardian of the barrels.

Like his predecessors, Sazaki trained in a prestigious restaurant in Kyoto to learn the fundamentals of Japanese cuisine. He also looked to Western cuisine for inspiration. “We have an outstanding variety of fermented foods in Japan, but none of them are presented as the main feature. They’re only served on the side or used for seasoning. So I looked at how cheese is used in European cuisine. Funazushi is also called ‘Japanese cheese,’ so I didn’t think it would be a stretch.”

And it wasn’t. The marriage of funazushi with the aroma of wheat was heavenly. With ingredients as simple as fish, salt and rice, funazushi was incredibly versatile. “I don’t want to limit the possibilities of funazushi to the boundaries of Japanese cuisine. Funazushi itself won’t change, but I want to explore its role within the modern Japanese diet. And maybe because the Japanese have become familiar with cheese, there are more and more people willing to try funazushi.”

The next morning, my alarm went off at 6:00 AM. Normally, I would’ve opted to sleep in, but there was something I had to see. Opening the shoji screen, I was rewarded with a sunrise that surpassed my expectation.

The sky was a translucent indigo. The rose colour of the horizon reflected on the lake surface, the waves rippling in indigo-pink stripes. After standing spellbound for a while, I decided to draw a bath. Floating in the boat-shaped tub, I gazed out at the gentle blue of the sky and the silhouette of the mountains enclosing Biwako. The faint outline of fishing boats glided along the surface of the water.

I wonder what’s for breakfast?

Written by Haruka Muta, Translated by Maho HARADA

June 21, 2017

Korian information

- TOPSTAYKorian

- TOPDESTINATIONSSHIGAKorian